This is the dilemma that snags Eddie Chambers’s account in his survey of black artists in British art. While I agree with Brett wholeheartedly, my critical concern is that if we focus only on the neglect, and attention toward the paintings themselves is thereby postponed, the danger is that we may end up reinforcing the oversight that isolated Williams from the narrative of post-war abstraction in the first place. Writing in 1988, critic Guy Brett indicted the “glaring injustice that Williams’s work was ignored and invisible in the country, Britain, where he has lived for nearly 40 years, as if it could not be compared with the work of his English contemporaries,” adding “There has … never been the opportunity to compare his handling of abstraction directly with his contemporaries like Alan Davie, Peter Lanyon, John Hoyland and Howard Hodgkin.” 2 DOI I frame my inquiry in this way because, although there is a valuable body of art criticism and art historical scholarship on Williams as my bibliography shows, the absence on the part of British institutions of a retrospective exhibition and monograph that would encompass his entire career reveals a degree of neglect completely at odds with the aesthetic innovations Aubrey Williams brought to twentieth century modernism through his practice of diasporic abstraction. A diasporic artist such as this enjoyed attachments to multiple places of belonging, but were such attachments ultimately incompatible with modernist internationalism, the worldview in which post-war abstraction was most widely interpreted? DOI 1 The term fits well for an artist born in British Guiana in 1926 who moved to Britain in 1952 and started exhibiting after studying at St Martin’s School of Art in London an artist who returned to visit Guyana at independence in 1966 and who established a presence in the Caribbean that led to a studio in Jamaica from 1973 to 1975, then a studio in Florida from 1977 to 1986, all the while maintaining his family in London, where he died in 1990. The word “diaspora” comes to us from the Greek verb “to sow” and by extension “to disperse” combined with the preposition for “over” which gives us the “dia” in diameter.

Approaching Williams’s abstraction in the interpretive context of diasporic “ancestralism,” a distinctive framework addressing the diaspora’s unrecoverable past, I suggest his Amerindian focus is best understood in terms of a “hauntological” mode of abstraction critically responsive to the moment of decolonisation in which boundaries that once defined the national, the international, and the transnational were being thrown into crisis.

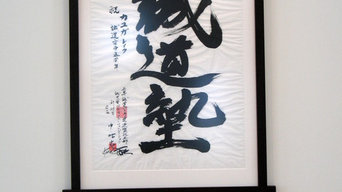

#Instant artist ithaca series

While retrospective exhibitions highlight the Olmec-Maya and Now series and the Shostakovich series produced during William’s circumatlantic journeys, both of which heighten abstraction as a medium of cross-cultural translation, the scholarship has left Williams isolated. But as he deepened his engagement with the indigenous cultures of the precolonial Caribbean during the 1970s-working in studios in Jamaica and in Florida-Williams was edged out of late modernism’s narrative of abstraction.

Moving to London in 1952, Aubrey Williams gained valuable distance on the Amerindian petroglyphs that inspired his abstract painting.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)